Until now, the Cardinals had never won a World Series with a team like this. A team that was lost, left behind and stranded in the standings. A team too proud and stubborn to accept the hopelessness of the situation. A team that fought back like no other has in franchise history. – Bernie Miklasz, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

There are some things in life that defy logic and reason. This past baseball season was one of them. As a Cardinals fan, this was a season of beauty and despair, jubilation and heartache, quirky plays and momentous comebacks. When the final out of Game 7 was recorded Friday night, a fly ball lifted high in the air towards the left field warning track that was caught by Allen Craig, I celebrated, hugged Andrea and my daughter, and yelled a cheer of joy and jubilation. But mostly I exhaled a sigh of relief, my emotions having been shot these past two months in a wild season of zany comebacks, devastating losses, and up and down swings. Invested as I was in this magical, historic season, the day after was anti-climactic, sad almost, as if something special and unique had been lost, forever extinguished to the dustbin of history, lost to the invisible forces of time and memory.

I am not certain if I really believe in destiny, or in miracles, but at least in the realm of baseball, if such things do exist, I witnessed it these past two months. To explain the Cardinals comeback in Game 6 of the World Series requires more than a mere knowledge of baseball folklore and physics. Having made three embarrassing errors earlier in the game, they trailed by two runs in the bottom of the ninth inning and were down to their last strike – their last breath really – when suddenly, magically, the forces of destiny overtook the cozy confines of Busch Stadium and willed the Cardinals to victory. The Rangers had on the mound one of the most reliable closers in the major leagues, Neftali Perez, a man who throws 99-mile-per-hour fastballs mixed with devastating sliders. But in a high intensity, pressure-filled at bat, with two strikes on him, David Freese, the Cardinals’ young third baseman, a hometown kid with two injury-plagued half-seasons under his belt, drilled a two-run triple off the right field wall to tie the game. I was delirious.

A few minutes later, when Josh Hamilton of the Rangers hit a two run home run in the top of the tenth to put the Rangers back on top 9-7, it appeared as if the Cardinals had finally run out of steam. We should have known better. Since August 25th, when the Cardinals were declared dead and finished by virtually everyone in baseball before going on a five-week run that is among the most brilliant and improbable comebacks in baseball history, this team has made clear they will fight to the finish. In the bottom of the tenth, with two outs and two strikes on Lance Berkman, the Rangers again one pitch away from a championship, Berkman hit a sinking line drive into the outfield to bring in the tying run, again. So, when Freese led off the bottom of the eleventh and hit a soaring 429-foot home run into the grassy knoll beyond the center field fence to win Game 6 in dramatic, walk-off fashion, it seemed almost inevitable, the forces of destiny having officially descended upon the Cardinals faithful.

“One of the great mysteries of sports is why some teams win and others lose,” writes Tyler Kepner of The New York Times. “Is it talent? Fate? Character? Karma?” The Cardinals seemed to have all of these things this year, although it did not seem that way in Spring Training when ace pitcher Adam Wainwright was injured and lost for the season, or when 17 key players at one time or another wound up on the disabled list throughout the first four months.

This may not be the most talented Cardinals team in my lifetime, but it may be the most memorable. The Cardinals were at times exasperating this year, blowing more saves than every other team in baseball except the Washington Nationals, and setting a National League record for grounding into the most double plays in one season. And yet, there were moments in mid-September that you sensed the possibilities. The Braves were slipping, descending into mediocrity, or worse, just when the Cardinals were putting it all together. When the Cardinals took three-out-of-four from the Phillies at Citizens Bank Park in mid-September, destiny became a possibility. And then, when the Phillies swept the Braves in the final three games of the season, the Cardinals also needing to win on that final day to even have a chance at the playoffs, there was a sense that the Gods of Baseball were believers themselves.

The rest is history now. After losing the opening playoff game to Roy Halladay, and down 4-0 in Game 2 of the League Division Series against Cliff Lee, who until then had a 72-1 career record in games in which his team led by four runs or more, the Cardinals came from behind to win, and then won two of the next three to upset the powerful and highly-favored Philadelphia team, beating them on their home turf in the fifth and final game. They were not supposed to beat the Milawaukee Brewers in the League Championship Series either, and when they lost Game 1 in Milwaukee, it seemed like their magic had run out. But then they rallied to win four of the next five games against the team with the best home record in all of baseball, and another miracle was in the books.

This World Series was exceptional in part because each team was so evenly matched. Except for Game 3, when Albert Pujols hit three home runs and propelled the Cardinals to a 16-7 win, the outcome of each game seemed determined by luck and fate and plays decided by a matter of inches. If Yadier Molina’s throw to second on Ian Kinsler’s steal attempt in the ninth inning of Game 2 is a millisecond faster or four inches lower, Kinsler is out and the Rangers probably lose Game 2. If Nelson Cruz gets a better jump on David Freese’s line drive in the bottom of the ninth in Game 6, or if he stretches out just a few inches more, he probably catches the ball and the Rangers win the Series in six games. If God had been a Rangers fan, he would not have allowed a rainstorm on Wednesday night to postpone Game 6 until Thursday and make it possible for the Cardinals to start Chris Carpenter on three days’ rest in Game 7.

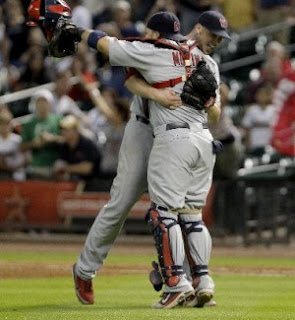

I cannot remember how many times this season, down the stretch in September, and throughout the postseason, that the Cardinals were deemed all but finished. But then Friday night in Game 7, when Jason Motte retired the final Rangers batter and the Cardinals jumped for joy, embracing each other like little kids who had just won a prize, the season finally came to a close with the Cardinals on top. “You gotta be a man to play baseball,” the great Roy Campanella once said, “but you gotta have a lot of little boy in you, too.” It has been tremendous fun to watch.

* * * *

As I look out my window this morning on our quiet tree-lined street in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, the ground is covered with snow and ice, winter having come early this year. A cold, harsh chill has replaced the crisp October air and the leaves cling desperately to their branches as if caught unawares by the forces of nature. Baseball is over now and life goes on, the long season but a collage of memories as the images of this wild and magical season quickly blend into the tide of baseball history. The Cardinals will stick around for a couple of days and enjoy the moment. They will bask in the glow of victory on Sunday afternoon as they parade down the streets of St. Louis to thousands of cheering fans, forever grateful that, for one brief and glorious moment, they could forget about the struggles of everyday life and together experience a baseball miracle. The Cardinals players will then head home for the winter, to rest, reflect, and prepare for next season, when they will endeavor to repeat the illogical, beautiful, exasperating, routine zaniness that is baseball.

In a few days, as I begin my annual sabbatical from baseball, it will again be time to rake the leaves. Meanwhile, I will join the ranks of the lucky few who can sleep with the knowledge that their team has won the last game of the season. In a quiet moment, when I have time to reflect, I will replay in my mind this miraculous season to better understand just how close things really were to a completely different, less satisfying result. And I will be forever grateful to the Gods of Baseball who, this season at least, allowed an outcome that may only properly be explained by destiny and miracles.