They have sweated beneath the same sun,

Looked up in wonder at the same moon,

And wept when it was all done,

For being done too soon.

--Neil Diamond

Andrea took me to Neil Diamond’s concert in Philadelphia

last weekend. It was the sixth Diamond concert I have seen in my lifetime. No

performer so captivates my spirit and touches my senses. At 74 years old,

Diamond still puts on a great show, and the familiarity of his songs and voice

still resonates with my musical soul. I have explained in a previous post the

origins of my admiration of Diamond and his music (“Young Child with Dreams: The Enduring Power of Music”) and, while he has lost some of his youthful cool

and dramatic flair, his connection with the audience remains authentic and

real.

About halfway through the concert, Diamond reminded us that

43 years have passed since he produced Hot August Night, a live recording from

1972 of a memorable performance at the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles. I bought a

copy of Hot August Night when I was 13 years old, and I have been a fan ever

since. It is hard to believe that nearly four-fifths of my life has passed in

that time, 39 years since I first saw Diamond perform in concert in 1976 at the

Spectrum in Philadelphia, a venue that no longer exists. I have gone from a

young teenager awkwardly trying to be cool (I failed miserably) to a

middle-aged man, father and husband, trying to make sense of a life that has

moved too quickly and keeps passing too swiftly.

I sometimes have difficulty processing the passage of time.

I take such pleasure in walking and writing, talking with friends about life

and joy, hopes and fears. I love books, fresh air, and the smell of grass on a

warm spring day. I envy those who seemingly glide through life with such conviction

and certainty, for I am ever searching, seeking, longing for answers that

continue to elude my grasp. I listen to the world, observe it, and take in its

abundant natural beauty, its blunt harshness, the diversity of its people, and

the many expressions of humanity and faith, longing and desire that this lonely

planet, a speck of dust in the vast universe, has to offer. And yet, so often I

obsessively try to stay abreast of the news, finish the next book, write the

next essay, that I miss the beauty and reality of life around me.

“The past isn’t fixed and frozen in place,” writes Parker

Palmer, a Quaker educator and weekly columnist for On Being. “Instead, its meaning changes as life

unfolds.” The regrets of our past – the selfish moments and unkind gestures –

may lead us to acts of kindness and generosity in the present. Knowing this

leads to humility, a much under-valued commodity in today’s overly aggressive,

hyper-competitive, self-promoting culture. And it allows us to better hope for

the future, to lessen the impact of lost time and the disappearance of youth.

Do you have hope for the future? someone asked Robert Frost, toward the end. Yes, and even for the past, he replied, that it will turn out to have been all right for what it was, something we can accept, mistakes made by the selves we had to be, not able to be, perhaps, what we wished, or what looking back half the time it seems we could so easily have been, or ought. – David Ray (“Thanks, Robert Frost”)

* * * *

Two weeks ago, the world lost a compassionate servant of

humanity, the Rev. John Steinbruck, whose vision of shalom and justice was

matched only by his passionate articulation of radical Christian love. I first

met Steinbruck in 1986, when he was the senior pastor of Luther Place Memorial

Church, a congregation with a social conscious located on the periphery of what

was then Washington, DC’s red light district. Steinbruck practiced biblical

hospitality and believed the church to be a place of refuge, where everyone was

welcome, from Washington power brokers to homeless drug addicts.

Starting in the early 1970’s, under Steinbruck’s leadership,

Luther Place opened its doors each night to hundreds of homeless women,

providing sanctuary for the oppressed and rest for the tired, weary, worn souls

of the District’s streets. “I don’t need five years of seminary,” Steinbruck

often said, “to know that when someone knocks on the door, you open it.” (See “The Saint in the City: The Life, Faith and Theology of John Steinbruck” and “John Steinbruck and the Challenge of Peace”). Steinbruck also was uniquely attuned

to the Jewish roots of Christianity and the common ground that existed between these two faith traditions, which was particularly important to me then as a

Lutheran in an interfaith relationship raising Jewish children. Steinbruck

regularly reminded his congregants of the harms committed historically by Christian

anti-Semitism and he involved Luther Place in vigils outside of the Soviet

embassy in Washington protesting the plight of Soviet Jewry. By doing so, he made Luther

Place a safe and welcoming sanctuary for me and so many others.

I will miss our talks and correspondence; the world will

miss his compassion and visionary leadership. If there is a Heaven, you can bet

John Steinbruck is there shaking things up.

* * *

*

On Tuesday night, March 17th, we joined a small gathering of

friends at the home of Ben Cowen and Mia Luehrmann to remember the life of a

very special young man, Natan Luehrmann-Cowen, who died five years ago when he

was tragically struck by a drunk driver while skateboarding after school a

block from his house. The universe was disturbed the day the world lost Natan,

and I have yet to fully come to terms with what happened. There are some things

that are too numbing for words. But at this dinner, at which those attending

engaged in a short ceremony and exchanged reflections and memories, there were

more happy memories than sad ones, and it was uplifting and inspiring to observe

the courage and bravery of Natan’s family – his loving parents Ben and Mia, and

wonderful son Aron (Natan’s older brother) – accept the sadness, embrace the

support, and carry on with grace and courage.

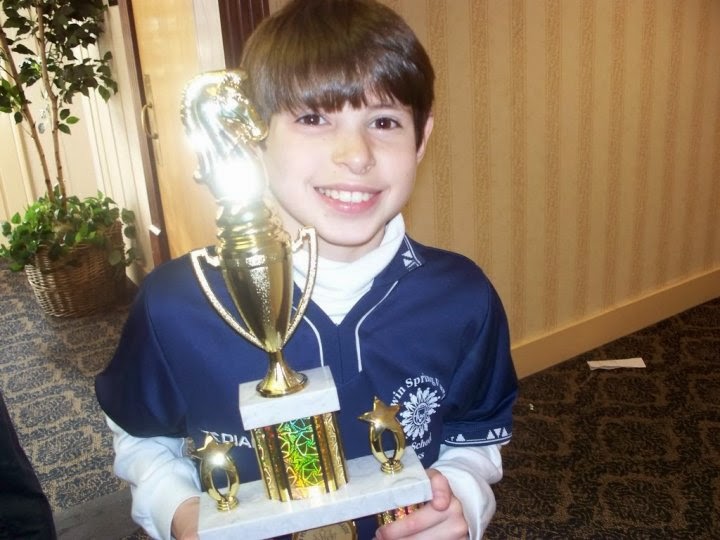

Natan was only 13 years old when he died. An exceptionally

smart, sweet, energetic soul with a zest for life that surpassed most mortal

humans, he was destined for greatness (“Natan Luehrmann-Cowen: Finding Meaning in Great Loss”).The loving unity displayed by Natan’s family the other night gives

witness to the truth that pain is an essential part of a meaningful, vibrant life.

However much it hurts, it is a direct outgrowth of love and joy and hope. “Wholeness

does not mean perfection,” writes Parker Palmer, “It means embracing brokenness

as an integral part of life.”

* * *

*

On Wednesday night, Andrea lost her dear friend Terry Lazin

(pictured above on the right). She was a kind, energetic woman of grace and

charm. Andrea and Terry met in 1974 at Temple University Law School, where they

became fast friends. Though they journeyed separately through life and, with the

passage of time occasionally lost contact, they remained lifelong friends, easily

picking up where they left off whenever they re-connected. I had the

opportunity to spend some time with Terry last summer when Andrea and I visited

her in Arizona, where Terry settled after a career in New York and Chicago. She

fought a heroic battle with cancer, but you would never know she was sick or

struggling, for her focus was always on others, her friends, her family, and her

three friendly, docile dogs. Even after her cancer diagnosis, she formed an

animal rescue foundation dedicated to preventing the abuse, neglect, and

euthanasia of homeless cats and dogs (Lazin Animal Foundation). She was an

immensely talented person, full of life, a positive energy force that the world

will greatly miss.

I am sad that the world lost Terry, sad for Andrea and for

those who were close to Terry and touched by her life along the way. But I am

glad that Terry and Andrea re-connected these past few years and grateful that we experienced Terry's graceful presence in her final months. Andrea

gave a beautiful tribute to Terry on a Facebook post after learning of Terry’s

passing. In discussing Terry’s unbelievable perseverance in the face of years

of cancer treatments, surgery, and medical setbacks, Andrea wrote that Terry always

“talked about the cancer as a gift that focused her on the importance of loving

the people and circumstances in her life. She implored all of us to not wait to

fulfill the promises we make to ourselves to do ‘in the future’ because you can

never be guaranteed a future. . . . Sleep well my heroic, beautiful,

extraordinary, loving friend. You left a wonderful legacy in this world and

unforgettable footprints on my heart.”

* * *

*

“Every hour I stand closer to death than I did the hour

before,” writes Parker Palmer. “All of us draw closer all the time, but rarely

with the awareness that comes when the simple fact of old age – or serious

accident or illness – reminds us of where we stand.” The cycle of life and the

mystery of death affect us all. I would like to believe that we are on this

earth to appreciate and embellish its beauty, to share the gifts we bring, to

laugh, to cry, to love. John Steinbruck, Natan Luehrmann-Cowen, and Terry Lazin

each in their own way touched the face of God and made the world a better

place. I have been inspired by their lives, grateful for their gifts, and

blessed to have been given the chance to experience life in all its dimensions.

Before saying good bye and sending us on our way following

his final encore last Sunday night, Neil Diamond remarked on the occasional harshness

of life and cold reality of the world outside, and he asked that we make an

effort to be kind to one another. It was a touching ending to an enjoyable

evening and served to remind us that, however comforting it is to seek shelter

in the cocoon of our individual lives, we have “all sweated beneath the same

sun and looked up in wonder at the same moon.” When the end of our lives draw

near, it will be the friendships we have made, the kindnesses we have bestowed,

the lessons we have taught and learned from each other, that will remain behind;

tiny footprints of memory in the lives we have touched along the way.

You need only claim the events of your life to make yourself yours. When you truly possess all you have been and done . . . you are fierce with reality. – Florida Scott-Maxwell (The Measure of My Days)